Objective:

The expectations of improvement among subjects participating in a Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) are one of the features most frequently associated with the placebo response. Consequently, it becomes a pivotal factor for understanding treatment effect, particularly in chronic pain RCTs such as Osteoarthritis (OA). There are multiple techniques to account for these expectations in studies, including staff training, subject training, or statistical adjustment for expectations. While the factors that create or modulate these expectations are numerous in the literature, there is no complete model to explain expectations. Understanding the sources of these expectations can undoubtedly lead to better management of the expectations and, therefore, of the placebo response itself.

Our analysis aimed to model subject expectations in two recent OA RCTs. In particular, the role of the subject profile and the sites interactions were assessed. This model would facilitate deeper insights into the underlying mechanisms of expectations and the discussion on optimal management strategies.

Methods:

The data from two clinical studies on OA were used for this analysis. The first study, involving 190 subjects, was used to develop a model of subject expectations. The second study, involving 133 subjects, was used to test this model.In both studies, subject expectations were measured using the MPsQ at baseline. Other features measured mostly by the MPsQ were used to model expectations and are categorized into psychological profile, psychological state, contextual factors (e.g., experience), interaction with the clinical site, average site effect, average country effect, and disease intensity of the subjects.

The influence of each of these groups on expectations was first evaluated descriptively in the first study. A predictive model incorporating all these groups of features was then constructed with the same data and evaluated by Cross Validation to avoid overfitting. This model was then tested on the second study.

Results:

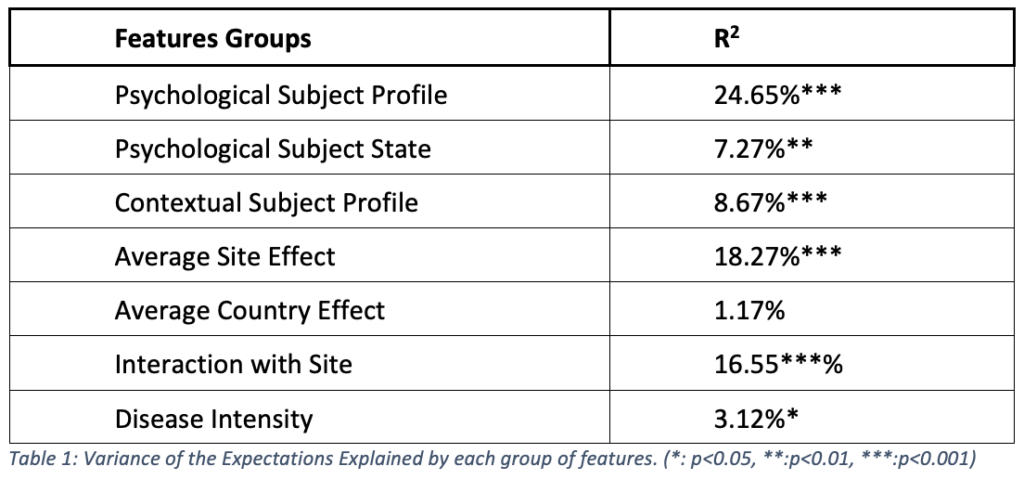

Table 1 presents the R2, the proportion of the subject expectations that can be explained by each group of features. They all explained a significant part of the expectations except for the average country effect.

By combining all these features, the predictive model significantly explained 35.7% of the expectations, leading to a correlation of 0.6 (p<0.001) between the predicted and the measured expectations. Tested on the second study, this model was significantly correlated with expectations, with a correlation of 0.49 (p<0.001). Finally, these predicted expectations explained as much the response in both studies as the measured expectations.

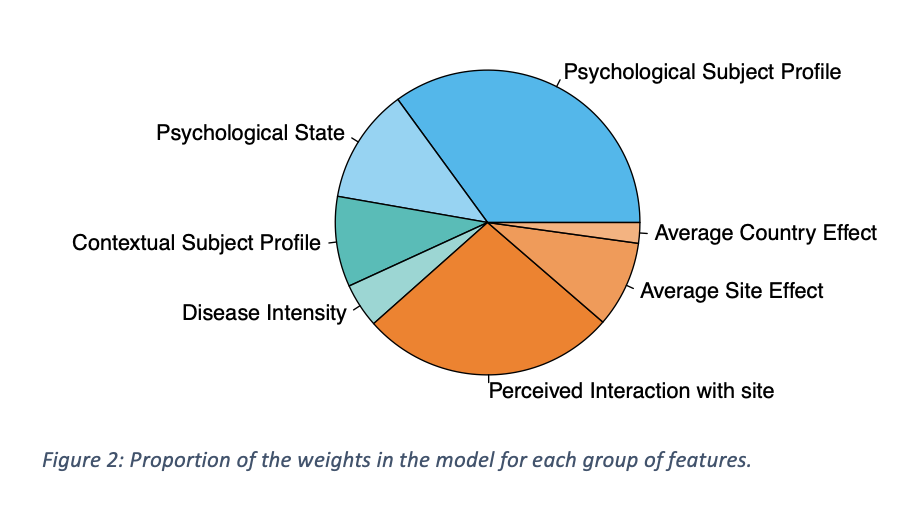

Figure 1 shows the proportions of the weights of the different groups of features in the model. The subject psychology explained close to 50% of subject expectations. Accouting for all the groups that can be associated to the sites (Average Site and Country effect, and interaction with site), the site contributed to over 30% to the model.

Conclusion:

Subjects’ expectations could be successfully modelled based on other baseline factors. In particular, the subject’s psychology (profile and states) and the clinical site (interaction with staff, treatment presentation, trainings, etc.) play pivotal roles. Both cross-validation and external validation of the model led to highly significant correlations between predicted and measured expectations. Moreover, the predicted expectations explained as much of the study endpoint as the measured expectations.

The model’s good performances allowed a qualitative comprehension of the expectations. As only one third of subjects’ expectations were associated with site or interaction with clinical staff, then any strategy aiming to mitigate expectations differences through site management could only partialy control of the expectations. Conversely, measuring the expectations and adjusting for them in statistical analyses would allow to address globally the expectations differences.