The expectations of improvement among subjects participating in a clinical trial are one of the features most frequently associated in the literature with the observed placebo response. Consequently, it becomes an essential feature to consider for better understanding the effect of a treatment, particularly in studies related to chronic pain. (1) There are multiple techniques to account for these expectations in studies, including site stafftraining, subject training before the start of the study, and applying an adjustment covariate.

While there are numerous methods to manage expectations, the factors that create or modulate these expectations are even more diverse in the literature. These include the subjects’ psychological profile (2), their state (stress, anxiety, depression, etc. (3; 4)), past experiences, beliefs, the quality of interaction with the clinical study staff, the positive bias induced by this staff, (5; 6)… Understanding the sources of these expectations can undoubtedly lead to better management of the expectations and, therefore, of the placebo response itself.

Given that Cognivia has been measuring subject expectations in clinical studies for nearly 10 years, it is now possible to leverage the accumulated data to gain deeper insights into the causes of this critical element. To do so, we analyzed subject expectations measured using the MPsQ (Multidimensional Participant-specificQuestionnaire) in several recent studies. The question we aimed to address here was relatively simple: Is it possible to explain/model subject expectations and, in particular, what is the contribution of the clinical site and the subject profile to the expectations they have when starting a study?

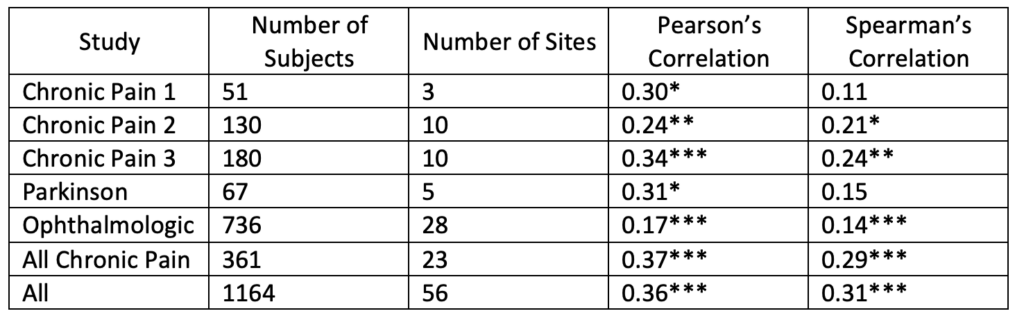

To address the problem in a straightforward manner, the first question was whether subject expectations could be explained by the expectations of the other subjects from the same clinical site. In other words, is there a correlation between the expectations of subjects in a clinical site and the average expectations calculated on that site, excluding the subject under consideration? To examine this, three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in chronic pain were considered, limited to sites with at least 10 subjects to ensure the relevance of the analysis. This represented a total of 361 subjects across 23 clinical sites for the three studies. Additionally, to complement this analysis with other indications, a study in Parkinson’s disease and an ophthalmology study were also considered.

As observed in Table 1, the correlation between a subject’s expectations and the average expectations is positive and almost always significant (only Spearman’s correlation for the two studies with few subjects/sites being nonsignificant). Such a correlation, around 30%, suggests that approximately 10% of the variability in a subject’s expectations is directly influenced by the clinical sites. These results confirm the impact of sites on subject’s expectations and the importance of monitoring or even controlling this factor.

Table 1: Number of Subjects, Number of Sites and Correlations between the expectations of a subject and the average expectations of the other subjects of his/her clinical site. (Significance: *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***:p<0.001)

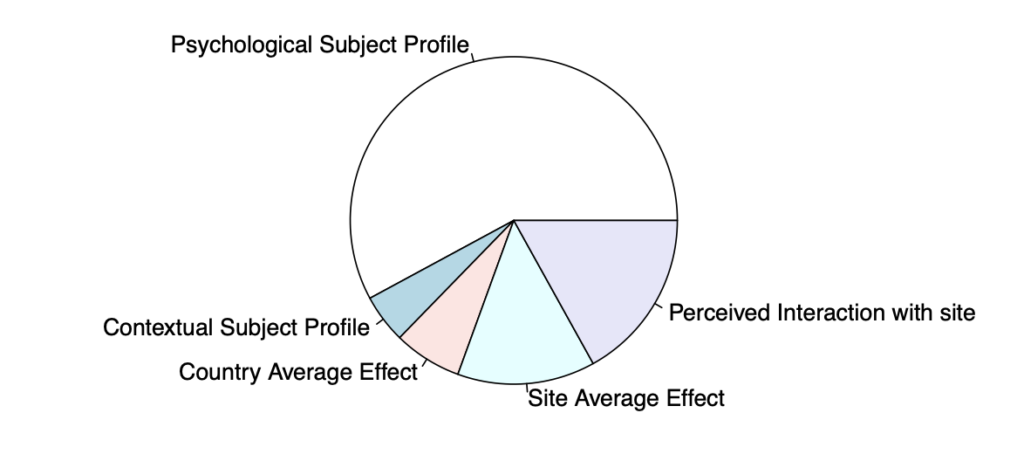

The pertinent question that follows is to understand the sources of the remaining variability. To do this, we can leverage the other elements of the MPsQ, which measure aspects of the subjects beyond their simple expectations, such as their psychological profile (traits and states), their perception of interaction with the clinical site, their experience, beliefs, and more. Using the data collected in phase 3 study in Chronic Pain (the largest and most comprehensive in terms of available features), we investigated the possibility of modeling subject expectations solely using MPsQ features. Since the study was conducted in multiple countries, the impact of each country was also assessed by using in the model the expectations averaged by country.

This modeling was pursued with a predictive, rather than descriptive, purpose. Through numerous resamplings, the model was evaluated each time on 10% of the subjects not used to build the model. The tested modeling was linear. The resulting predictive model was highly significant, with 35% of variances explained corresponding to a correlation around 60%. Considering that a questionnaire’s test-retest correlation is considered good if it is 80%, this result indicates that beyond the measurement noise associated with the subject, this model explains the majority of expectations.

What does the model contain? To gain better understanding, we grouped the features into the following categories:

- The subject psychological profile

- The subject contextual profile (experience, beliefs)

- The average expectations in the subject country

- The average expectations at the subject clinical site

- The perception of the subject interaction with the clinical site

The importance of each group in the model is presented in Figure 1 illustrating the relative importance of the features in the modeling. While this evaluation method is imperfect, it provides a first overview of each element’s contribution to the subject expectations. The average expectations at the subject clinical site represent a substantial part of this model (13-14%). Additionally, other elements related to the site also play an important role, such as the site’s interaction with the subject (16-17%). Furthermore, based on this analysis, it is difficult to determine whether the average impact of countries is due to a common effect of sites or, conversely, should be seen as a shared characteristic related to the specific attributes of subjects from that country or even linked to the manner in which the study was specifically conducted in that country (through differential management). Regardless, it appears more straightforward, at least initially, to consider this as an intrinsic property of the sites comprising each country. This would raise the importance, in the model, of the features associated to the site to approximately 37%. Leaving 2/3 of the explained variability associated to the profile of the subject.

This analysis confirms the role played by the clinical site in shaping subject’s expectations. This justifies the interest in training methods for subjects and/or clinical staff to control the level of expectations. However, it is essential to differentiate between the two methods. Indeed, site training may better harmonize subject’sexpectations across sites, reducing the site’s contribution to subject’s expectations (and thus their variability). Conversely, one may question whether subject’s training, regarding their expectations, risks increasing variability between subjects. Indeed, the intensification of the process to which subjects are exposed could potentially lead to differences in how they experience this process.

Regardless, the question must also be raised about the limit to which a site should focus in reducing expectations. As previously demonstrated and in line with the literature (6), the quality of the relationship with the site and clinical staff, as perceived by the subject, plays a positive role in shaping expectations. This relationship is also crucial for maintaining subject adherence to the study in which they participate (7). This may explain why expectations, through their correlation with the patient-therapist alliance (6), are sometimes associated with greater subject involvement or engagement in treatment, leading to better outcomes (8; 9). Reducing expectations could, therefore, have a counterproductive effect given the significance of adherence in RCTs. As suggested by Langford et al. (1), it is, at least, important to consider these expectations as anadjustment covariate in the analysis of RCTs. This is precisely why Cognivia, as part of the MPsQ, has been measuring these expectations for a decade: to use this measure for adjusting expectations through its composite covariate, Placebell.

At last, this analysis also illustrates that the MPsQ can detect genuine site effects. By employing the models presented above, it will even be possible to understand the true proportion attributable to sites (and not to the profile of the corresponding subjects). This analysis can undoubtedly have a post-hoc or monitoring purpose to gain a better understanding of the study through its data. It can be instrumental in improving the conduct of subsequent studies through relevant feedback. Hence, Cognivia’s desire to offer sponsors the ability to analyze site heterogeneity through key measures in the MPsQ is fully justified. In conclusion: it is possible to use machine learning to enhance data comprehension, rather than to its detriment.

References:

1. Expectations for Improvement: A Neglected but Potentially Important Covariate or Moderator for Chronic Pain Clinical Trials. Langford, Dale J., et al. 4, 2023, The Journal of Pain, Vol. 24, pp. 575-581.

2. Dispositional optimism predicts placebo analgesia. Geers, Andrew L., et al. 11, 2010, Journal of Pain, Vol. 11, pp. 1165-1171.

3. Treatment Expectancy and Credibility Are Associated With the Outcome of Both Physical and Cognitive-behavioral Treatment in Chronic Low Back Pain. Smeets, Rob, et al. 4, 2008, Clin J Pain, Vol. 24, pp. 305-315.

4. College Counseling Center Clients’ Expectations About Counseling: How They Relate to Depression, Hopelessness, and Actual-Ideal Self-Discrepancies. Goldfarb, Dori. 2002, Journal of College Counseling, Vol. 5, pp. 142-152.

5. Patient expectations in placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials. Stone, David, et al. 1, 2005, Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, Vol. 11, pp. 77-84.

6. The Association Between Patient Characteristics and the Therapeutic Alliance in Cognitive–Behavioral and Interpersonal Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa. Constantino, Michael, et al. 2, 2005, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 73, pp. 203-211.

7. Enhancing adherence in clinical research. Robiner, William N. 2005, Contemporary Clinical Trials, Vol. 26, pp. 59-77.

8. Expectations. Glass, Carol, Arnkoff, Diane and Shapiro, Stephanie. 4, 2001, Psychotherapy, Vol. 38.

9. Expectancy, Homework Compliance, and Initial Change in Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety. Westra, Henny and Dozois, David. 3, 2007, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 75, pp. 363-373.